As far as hot topics in literacy go, the science of reading makes the top of the list. If you google the term, you get a myriad of results, from training to programmatic promises. This article reviews the science of reading and offers three considerations for teachers to align classroom instruction to the science of reading. Plus access an exclusive on-demand webinar to learn even more on the topic of the science of reading.

A Look Back at the Science of Reading

It has been interesting to me to feel the fire of the conversation around the science of reading. It often feels like a debate, one that you must take sides on. Yet the conversation has been happening for years.

The science of reading is the collection of excellent research that leads to an understanding of how students learn to read. The science (known understandings, results, data, and so on) about how humans learn to read has long been studied. While nuanced understandings and new information does filter in, the baseline understandings have largely remained the same.

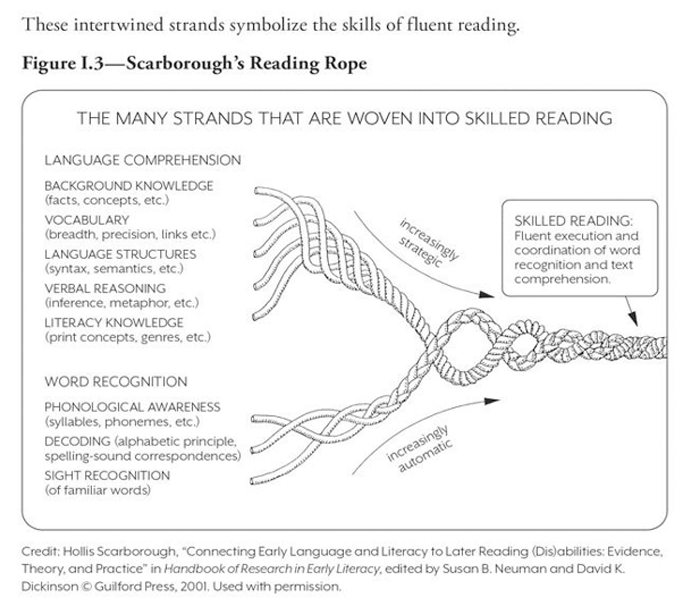

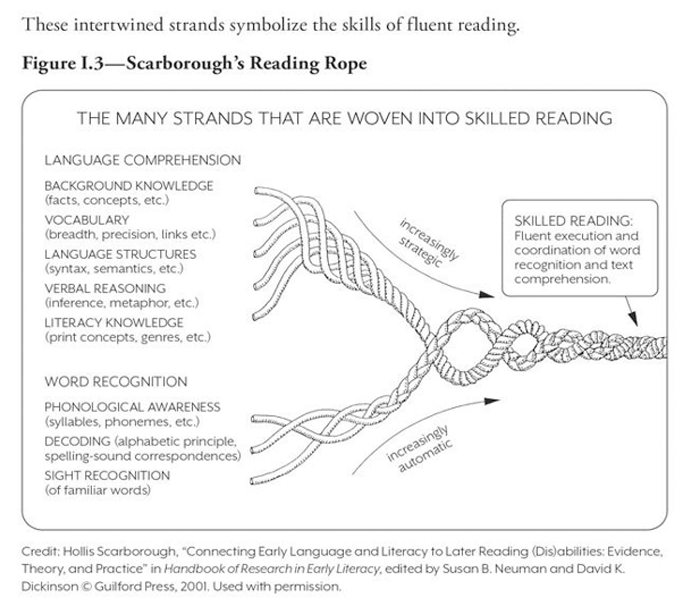

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

In 2002, in a workshop in my home state, I used pipe cleaners to model Dr. Hollis Scarborough’s reading rope. This is a common activity and bulletin board topic in schools digging into the science of reading now. Why? It is a seminal work.

The reading rope was first presented in 2001, the same year that the five essential elements were highlighted by the esteemed National Reading Panel. Much of what educators do already uses the evidence. The next best steps are to provide opportunities for continued learning, to fine-tune instructional practices, and let go of practices contrary to the body of research.

Three Considerations for Every Teacher to Align to the Science of Reading

To help all teachers align their instruction to the science of reading, let’s examine three considerations that can greatly impact student achievement by ensuring that evidence-based opportunities exist in every classroom. We are going to focus on the comprehension strands that weave together the reading rope. While we are not discussing the integral and important work of developing word recognition, we are not discounting it either. The process of word recognition is another blog article for another day.

1. How is this unit/lesson intentionally designed to build knowledge and vocabulary?

Knowledge is power. The more you know, the more able you are to make connections to new learning and understanding. Teachers often consider background knowledge to be facts and information that students have so they can comprehend content-area informational text. However, background knowledge is more than just facts. It is a composite of all the experiences, vocabulary, and personal interests and interactions students have ever had.

Background knowledge and understanding impact how students engage with and understand text. Thus, one significant priority in developing students who comprehend text is ensuring that students have adequate knowledge and understanding to support them as they learn and engage with new content. Students have a working and growing knowledge base. For students to build knowledge, they must have regular access to rich and captivating informational text and stories. Importantly, students will attain more information and build more background when their learning is structured to introduce and explore specific topics and ideas.

For example, second graders can dig into learning about plants: they can engage with informational books about plants, articles about plants, and a story that takes place in a rooftop garden, as well as pictures and short video clips that discuss plant life cycles. This approach supports the building of knowledge and allows students to develop a robust understanding of a topic that is fundamental and that supports learning across contexts.

How to do it

First, set up students for success by ensuring that all students know what they need to know. What is the purpose of this learning? How does it connect to what they already know? Provide students with deep opportunities to learn about highly engaging and relevant topics, those that will transcend into understanding about other things. When students are engaged in a unit, learning about SOMETHING, ensure they have access to multiple books, videos, pictures, vocabulary words, graphic organizers, and hands-on opportunities to learn.

For example, if students are learning about plants

- plant some quick-growing plants

- keep a journal

- watch videos about plants

- look at and label pictures of plants

- look at diagrams of the plant life cycle

All students can benefit from read-aloud, to engage with complexities they may not be able to tackle independently. Opportunities to self-select texts that continue to build knowledge and vocabulary about the topic will enhance both engagement and understanding.

2. What strategies are in place for my students to have consistent access to complex text?

Complex text is an important way to be certain that all students develop knowledge that will support them as they continue to make connections with their learning. However, I haven’t been in a room of teachers (not yet anyway) that were all confident that their students could independently navigate complex text. Tackling this challenge is not easy, but there are many strategies to support all students.

How to do it

First, recognize what makes text complex. To keep it simple, let’s recognize these four characteristics. Certainly, these are not the only things that make text complex, but they certainly are a great place to start.

|

Vocabulary

|

- Explicitly teach how authors support word knowledge within text

- Explicitly teach words that students need to be successful with the text

- Provide students with student-friendly definitions of words

|

|

Background Knowledge

|

- Support students making connections with previous knowledge

- Provide students with a cheat sheet that supports their background information

|

|

Syntax

|

- Explicitly teach how words, phrases, and sentences work

- Dissect mentor texts to highlight the nuances of syntax

|

|

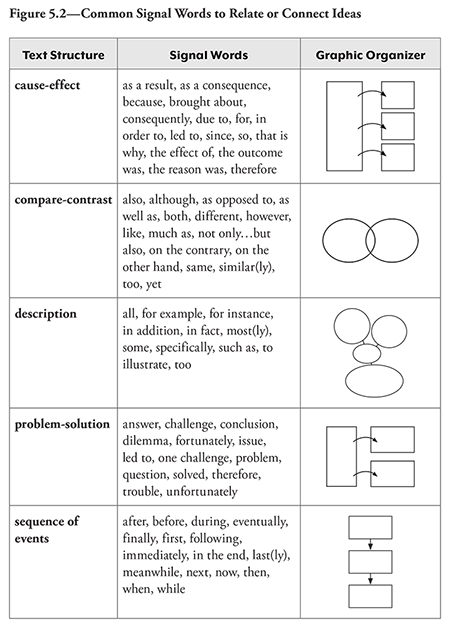

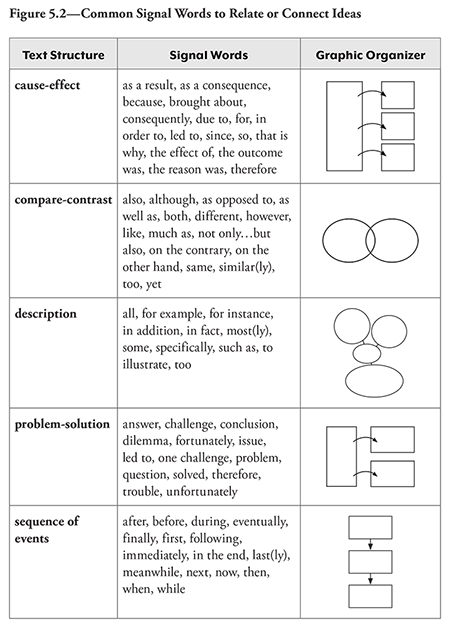

Text Structure

|

- Provide graphic organizers to support text structure

- Supply students with signal words that help identify text structure (see example below)

|

When these are recognized as the barriers to success with complex text, finding ways to support students becomes much more realistic.

When these are recognized as the barriers to success with complex text, finding ways to support students becomes much more realistic.

3. How are my students engaged in authentic opportunities to collaborate, discuss, and write about what they are learning?

Purposely plan for focused discussions on text and knowledge being built. Discussing what has been read during and after reading allows students to reflect on the information in the text, clarify confusing information, and build knowledge in a collaborative setting. Discussions should be led by the teacher and students. The teacher may have a series of questions for the class or group to consider, or students may devise their own questions to discuss. Support collaborative discussions with questions that allow for multiple responses and varied ideas. Teach protocols that support discussions.

How to do it

|

Campfire Discussions

|

Students are in small groups. Each group is given a topic, quote, question or prompt related to the learning target. This is placed in the center of the group as the “campfire.” Each student individually responds on a sticky note, and then places it by the campfire. This leads to a discussion around the campfire.

|

|

Seminars

|

Students use evidence from a specific text to understand what the author is working to convey. Students build upon one another’s ideas, with little to no intervention from the teacher.

|

|

Casual Brainstorm

|

Students are divided into small groups. In their groups, they respond to prompts or questions on various poster papers around the room. They can also respond to their peers in writing on the posters

|

With these three considerations, your classroom is using the science of reading to provide high-quality instruction. Is that it? Of course not. The science is both wide and deep. We all have things to learn. This is simply a quick starting point to ensure you’re aligning instruction to the science of reading, offering evidence-based opportunities and research-based instruction for all students in your classroom.

When these are recognized as the barriers to success with complex text, finding ways to support students becomes much more realistic.

When these are recognized as the barriers to success with complex text, finding ways to support students becomes much more realistic.